Andrew Copson of the British Humanist Association has written a helpful analysis of the latest European Court of Justice ruling on religious symbols in the workplace. It looks to me as though the new ruling does muddy the waters though.

A corrective for the ‘headscarf ban’ hysteria yesterday: https://t.co/gW6JRp1n6M @guardian @BBCNews

— Andrew Copson (@andrewcopson) March 15, 2017

In my opinion, it should only be possible for employers to ban the wearing of clothing or jewellery that is likely to get caught in machinery, be grabbed and pulled by disturbed clients, prevent the wearing of appropriate safety gear, or otherwise endanger the wearer.

In some countries, such as France and Belgium, they have the principle of Laïcité, which

“encourages the absence of religious involvement in government affairs, especially the prohibition of religious influence in the determination of state policies; it is also the absence of government involvement in religious affairs, especially the prohibition of government influence in the determination of religion”.

That sounds like an excellent idea, but I don’t see what it has to do with restricting people from wearing religious garb in public, or in the workplace, although laïcité was used as an excuse to ban the burqini from some French beaches, despite the fact that its designer intended it to promote inclusion.

As a Wiccan, I am wearing a pentagram ring today, but that should be no concern of anyone but me. I’m a web developer, so wearing a pentagram ring does not impede my work in any way. No-one has ever actually noticed my pentagram ring in the workplace (though I am out of the broom closet at work), and I am not wearing it to make converts, but as a personal statement.

The ECJ ruling concludes that bans on wearing religious symbols is not direct discrimination, but may be indirect discrimination (I think that’s what it says, it is confusing).

Andrew Copson explains the difference between direct and indirect discrimination:

Essentially in equality and human rights law there are two types of discrimination. Direct discrimination, as it relates to religion or non-religious beliefs, is where you have a policy that targets someone because of their religion or belief.

Indirect discrimination is where you have a policy that does not target someone because of their religion or belief per se, but it nonetheless puts individuals of particular religions or beliefs at a disadvantage, when compared to those of other religions or beliefs.

However, the ECJ ruling adds that attempts by companies to maintain “neutrality” by banning religious symbols is legitimate – but it is only legitimate if it is applied equally to all religious symbols/dress etc, not targeting a particular group (e.g. Muslims). If it targeted a particular group, then it would be direct discrimination.

Nevertheless it will disproportionately affect groups with more distinctive religious dress, such as Muslims and Sikhs. That is surely indirect discrimination, then?

And since this ruling gave rise to tons of headlines reporting it as a ban on Muslim headscarves, it adds to the climate of fear and makes Muslims feel targeted.

It would have helped if the European Court of Justice had issued a press release that clearly and simply explained what they were saying in the ruling, which the summary document completely failed to explain.

Given the extreme sensitivity of the issue and the rising tide of Islamophobia, clarity is needed, as this headline shows:

Headscarf ban: ‘What a woman wears is her choice’, World at One – BBC Radio 4

Chair of the Women and Equalities Select Committee calls for ‘urgent clarity’

The principle should be that everyone can wear what they want as long as it harms no-one. Clothing with slogans inciting hatred would thus not be allowed, but religious garb would be allowed, provided it doesn’t endanger the wearer by being liable to get caught in machinery or be grabbed by unruly clients. This would reflect previous rulings by the European Court of Justice.

The decision as it stands appears to pander to the prejudices of customers who might complain about having to deal with a sales representative wearing a headscarf, or a turban, or some other religious garb.

Some people have tattoos. Some Pagans, Quakers, and Unitarians (and maybe other religious groups) have tattoos with spiritual or religious significance. Many workplaces stipulate that staff should cover up their tattoos, which is also discriminatory.

I don’t want Muslim women to feel that they have to wear a headscarf – it should be a genuine choice – but I don’t think that forcing them not to wear a headscarf is the right approach either. As a feminist, I want women to be able to choose what to wear, and not be made to follow restrictive dress codes, whether that’s forcing us to wear high heels, make-up, and nail varnish, or forcing us to wear a headscarf, or not to wear a headscarf.

Men should also not be forced to dress a particular way, such as wearing a tie, a suit, having short hair, not wearing make-up, or whatever else they are subjected to in the way of restrictive dress codes.

And people should not be forced to adhere to a particular gender expression in their clothing and hairstyle choices either.

The key word here is choice. If it harms no-one, do what thou wilt.

![Interfaith banner by Sean on Flickr [CC-BY-SA]](https://dowsingfordivinity.files.wordpress.com/2017/03/2295355354_e65354babd_z.jpg)

Interfaith banner by Sean on Flickr [CC-BY-SA]

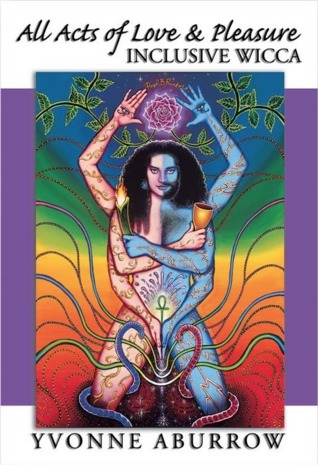

If you enjoyed this post, you might like my books.

Well said!

LikeLiked by 1 person

My feeling on this issue are complex. I support religious freedom and expression on the one hand. I also strongly support secularism and the spirit of what I think the French mean by Laicete. French secularism in some ways mirrors our own legal and cultural regime of separation of church and state in the U.S. More than that though, it is rooted in the revolutionary ideals of egalitarianism. Founders of the modern nation really wanted to bring an end to the use of religion as a sort of marker of caste and a kind of tribalism. In this new vision, you are not French-Catholic or French-Protestant or French-Jew. You are first and foremost just French, and as French as anyone else regardless of whatever other identifiers you have.

That has been their social compact for well over two centuries and arguably has served them well. That doesn’t mean social compacts are immune to revision or challenge, but neither should they be summarily dismissed or ignored if we are to understand the context of an issue like this. Not all of this debate is driven by racism or simple Islamophobia.

Freedom of choice also becomes somewhat murky in the context of headscarves and the more extensive sorts of veils worn in Islamic cultures. There are plenty of Mulsim women who choose to wear these things purely out of their own will and see it as empowering. That’s great.

There are also many others who do not have a choice in the matter. In most Middle Eastern and South Asian Islamic countries, hijabs or other coverings are compulsory. Sometimes through written legal code, and sometimes through street level cultural coercion in which unveiled women are subject to verbal or physical harassment, beatings, sexual assault or murder. These sorts of threats do not always disappear simply because a Muslim community relocates and establishes itself in, say, a Paris suburb. For a variety of reasons, including racism, many European Muslims do not integrate with the host society.

If headscarves and similar dress are accommodated as choice, will women in these communities truly also have the freedom not to wear them? Further, what are the long-term implications of retooling the French social compact in a way that makes public religious piety a person’s primary identifier and measure of virtue? When Muslims become a majority in Europe, as they will at least in pockets later this century, will freedom of expression become expectation of expression and then mandated expression? Under a regime of what might be called “un-secularized” Islam, the future for Pagans and pretty much any other religion is pretty dark. None of the countries these folks hail from recognizes any significant freedom of religion.

That said, I don’t know that heavy handed bans on religious symbols or clothing are they answer. They have the potential to make things worse. I don’t know what the answer is, only the basic dimensions of the problem.

LikeLike

Given the current climate of hostility to Islam and its expression, I think that any sort of scenario where Muslims become dominant is unlikely. It’s also worth remembering that many Muslims in Europe have left their countries of origin because they were persecuted there for some reason – so they are hardly going to want to reproduce the environment of the country they fled.

LikeLike